Edited by Malini Adkins

In partnership with the USC Keck School of Medicine, LA General Medical Center’s Women’s Clinic, and the Wellness Center at the Historic General Hospital, the “Virtual Reality Memorial” (a.k.a. Immersive Memorials) project aims to create media arts memorial pieces for gynecological cancer patients. Additionally, letters are produced in conjunction with these artworks, which are made to be addressed to the patients’ loved ones. Supported by USC Arts in Action, this unique initiative highlights the role of media arts in expressing and preserving legacies.

Professor of Cinematic Practice and Director of the Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center, Marientina Gotsis, talked about how the initial seeds for this idea emerged from a deeply personal experience nearly twenty years ago.

“My closest college friend, who was dying of cancer, asked me to make a bespoke website for him to showcase his architectural work. At his wake, I gave a copy of the website burned onto a CD-ROM with a cover made of his favorite photograph,” Gotsis reflected. “A decade later, in one of my experimental practicum classes, we explored end-of-life legacy artmaking with VR while one of the students produced short immersive interactives on behalf of the others over the course of a few days.”

Most serendipitously, Gotsis received an email from USC and LA General gynecologic oncologist Dr. X. Mona Guo, MD, regarding a project that proposed interviewing as a process to help gynecological cancer patients create legacy pieces for their families and friends.

“During my training, I’ve been stricken by how abruptly end-of-life comes for patients, despite our best attempts for preparation,” Dr. Guo wrote in her email to Marientina back in September 2023. “One thing that has helped at Keck is writing letters to their families (specifically children) to be opened at future life events for which the patient could not be present for. However, at LA General, many of my patients cannot read or write, so creating short video clips on their phones has been helpful. I wish I could help more patients do this.”

Dr. Guo continued. “I saw an email from Arts in Action to fund art projects, and thought I’d explore this further. I would like to pursue a project to help terminal cancer patients create professional video and/or audio memoirs and messages to their families (and vice versa, for families and friends to create messages for their loved ones), ideally before the end of life.”

“When Dr. Guo reached out with her idea to apply for the Arts in Action award, I told her I had been waiting for her for a decade,” Gotsis admitted.

Robin Romans, the Associate Vice Provost for Arts and Academic Affairs at USC, quickly recognized the significant impact of the Immersive Memorials project after reading the proposal.

“It’s hard sometimes to visualize how a proposal is going to look in terms of practice,” Romans said. “But this one had a pretty good idea that [the students and faculty from the interactive media program] were going to work closely with some of the healthcare providers and patients.”

As a result, the project provides a distinctive platform for underrepresented patients to share their voices, offering a new perspective on palliative care and exploring innovative approaches to specialized medical support.

“I could tell that for the patient themselves, it was cathartic to kind of go through this,” Romans commented. “What was really impactful in this case is when I saw how engaged the medical teams were…That was really meaningful.”

The Early Stages

Catherine Dugan, a Keck medical student participating in the Immersive Memorials, received information about the project from Dr. Guo in early 2024.

“I really didn’t know much about it when I signed up to do it. I just thought it was a really meaningful idea, especially when palliative medicine resources are somewhat limited.” Dugan recalled.

Dugan described palliative medicine as quality-of-life medicine. It’s a way to manage the symptoms for a patient as their treatment evolves from what is labeled as “curative” intent treatment to “palliative treatment.” When that shift occurs, the medical team can no longer cure the patient’s illness. Instead, their goal is to provide comfort and support.

“At that point, we’ve expended all of our curative approach, curative treatment options, and there’s nothing we can do anymore to stop the advancing of the disease,” Dugan explained. “And so what our attention turns to is how we can improve the person’s experience of their disease?”

Upon signing up for the project, Dugan then went on to interview her assigned patient, who had already consented to being involved in the project. Dugan accomplished this approach by incorporating evidence-based frameworks for end-of-life wishes, including “Dignity Therapy” and the “Stanford Life Review.”

“What we were trying to figure out was what standardized questionnaires there were that had validation,” Dr. Guo clarified. “These two that we found with ‘Dignity Therapy’ and ‘Stanford Life Review’ have all been translated and validated. So, we were able to use these questions for the interview.”

Through these formats, the medical professional leads patients through a series of questions that provide an opportunity to record a patient’s most treasured moments. Furthermore, patients are encouraged to express their gratitude and messages for their loved ones before finally saying goodbye.

“We interview a patient every week in the hospital, oftentimes as part of [medical school] coursework. But, it was my first experience dealing with a patient where they know there’s nothing else that can be done,” Dugan said.

Once Dugan had conducted two standardized interviews with one of the patients, Felicity*, who consented to being involved in the project, the arts and medicine team met to transform Dugan’s interview transcripts into detailed documentation for the patient’s letter and media art pieces.

Development + Impact

Written from the patient’s perspective, the goal of creating letters for patients is to chronicle their interview responses into a personalized message for their loved ones. This presents an opportunity for patients to take ownership of their narrative and obtain closure for both themselves and their loved ones.

One of the writers on the arts team, Frank Perazzini, was introduced to this process when he entered the MA program for Cinematic Arts (Media Arts, Games and Health) as a progressive student.

“My initial impression of the project was that it was an entirely new world of narrative I had just discovered,” Perazzini stated.

The writers from that team consistently met with Felicity to capture the right tone in each drafted material and incorporated her edits into the final version of her letter. This stage was intended to embed a deep sense of collaboration and open communication.

“I was really grateful to apply the writing skills I had learned in my undergraduate work towards something as special as VR Memorial,” Perazzini said.

The finalized written material went on to serve as a springboard for Felicity’s memorial media art piece.

“A personal goal I had for this project was to capture the essence of the letters written by the patients to their families in their VR Memorial project…” Perazzini affirmed.

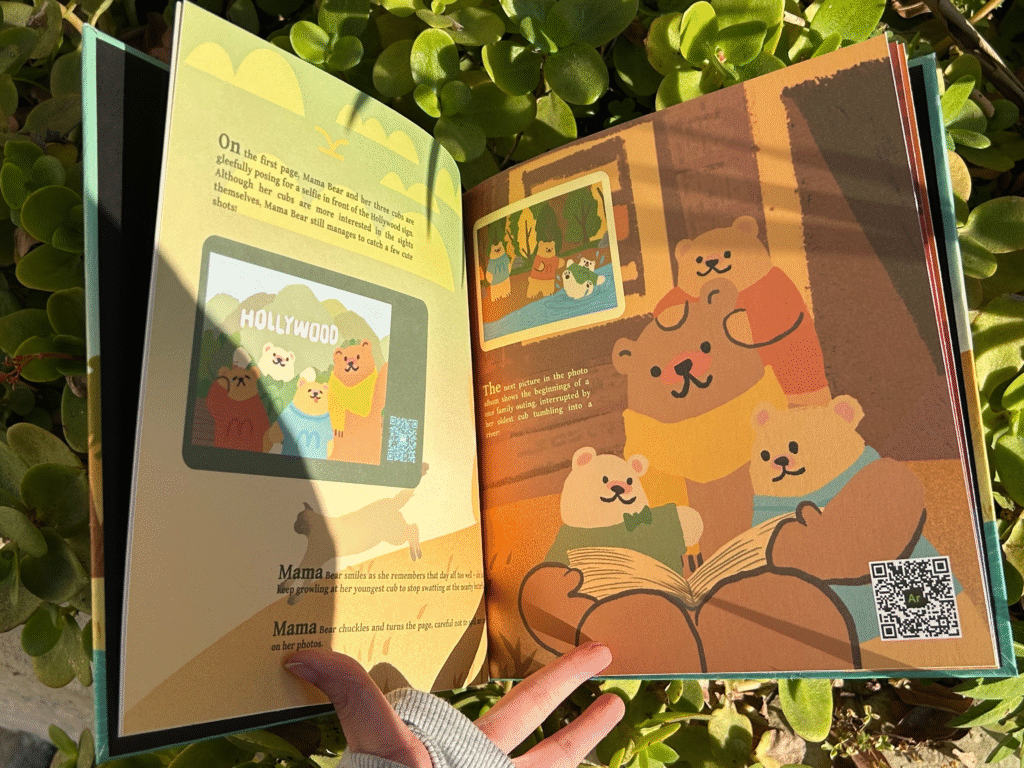

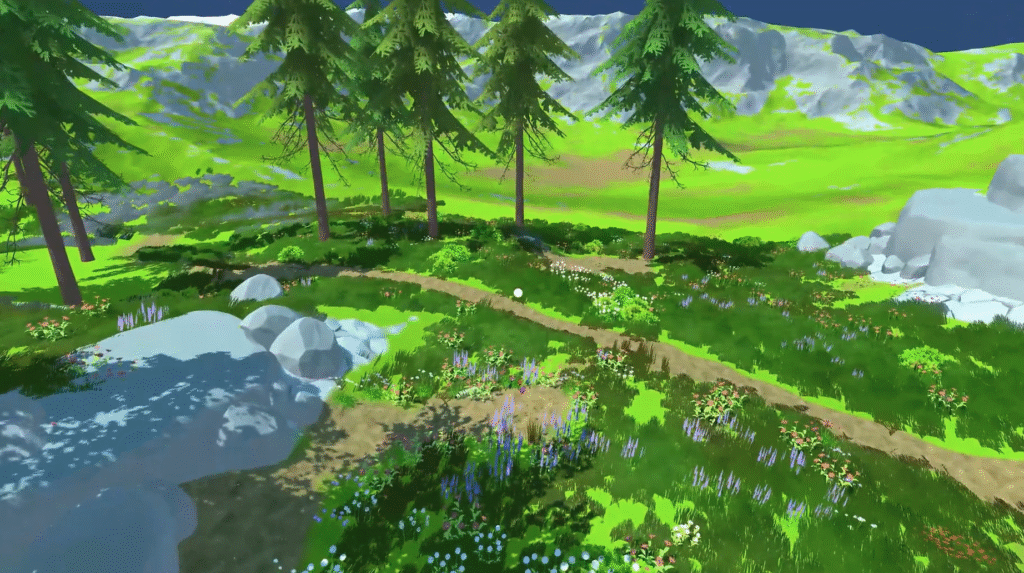

At this point in the project, the team had begun onboarding another patient, Dina*. As soon as the patients provided their final seal of approval, the written content went on to be used as the “heartbeat” for Felicity and Dina’s design pieces, which were created to capture the spirit and life experiences of both Felicity and Dina. Ju Sun, a first-year MA student in the Cinematic Arts (Media Arts, Games, and Health) program, worked on Dina’s artwork from start to finish.

“Specifically for Dina’s project, I mainly focused on the development of the VR experience. It’s like a hackathon; everybody sits [in the lab] and we work together, and it’s a really good experience,” Sun explained.

It is essential to note that these design creations are no longer limited to VR, allowing the art team the flexibility to explore other storytelling mediums.

“I think overall [the VR aspect] is less important because it doesn’t really matter what the medium is,” Dr. Guo added. “It’s about a memorial, it’s about creating a legacy. It’s about [an art] piece that represents this patient’s legacy, what they want their loved ones to remember them as, and what they want their loved ones to remember of them.”

Once the team decided to expand their ideas beyond VR, they developed two distinct pieces that embody the individual narratives of both patients.

Dina and Felicity were invited to review the content at each stage of development before giving their approval. Sun remarked, “It’s definitely a very valuable experience because we are kind of memorizing somebody’s most valuable experience, life experience, and making it a gift to their loved ones. And I think that’s very meaningful for me personally. I think I just had a lot of motivation to do this.”

The creation of each memorial art piece has led to significant personal growth and reflection for the design and development team. As a result, Felicity and Dina’s core narratives have begun to illuminate their legacies.

Moreover, this project has broadened the context within the healthcare system, highlighting the importance of the project’s foundation.

“I have a new understanding of what this medical system needs…it’s like we need to care more about the narrative part of how we communicate with patients and do more to support them,” Ju reflected.

One of the interpreters for gynecologic oncology patients, Rocio Rodriguez, shared her insights on how the project impacted both her and the healthcare system.

“I’m going to be really open with you. When I first read about the project and what the project wanted to do, I thought, ‘Oh my God, no! This is going to be so painful.’” Rodriguez admits. However, despite her initial hesitation, Rodriguez agreed to help with offering her translation services for the letter-writing process. “…Once I started reading their letters, and understanding more of what [the team] was doing, I went to the memorial at the Wellness Center, [and] I was thinking this is amazing. This is amazing because these ladies deserve that and more.”

Approximately 70% of the patients in the LA General gynecologic oncology clinic report Spanish as their preferred language. Considering the existing literature, including these patients in this initiative was essential.

“A big reason why patients who are not English speakers are excluded from a lot of medical research is because translations are really expensive…it’ll often cost thousands of dollars per document, and it’s hard to come up with that money,” Dr. Guo stated. “But [LA General] told us to send stuff to [their] language service department, and they will translate everything. And that was a collaboration that was extremely meaningful.”

Rodriguez went on to explain how personally working on the project as a translator affected her on a deeper, emotional level. “I can honestly tell you that the letters that I’ve had to translate, I was crying while I was writing because it is so powerful. It’s so powerful as a human being.” Rodriguez said.

Nonetheless, the tangible outcome from this project does not go unnoticed by her, “I think there are so many things that can come out of these,” Rodriguez stated. “I think the most important thing that you have to remember, that we all have to remember, is that they’re giving the time and attention that they didn’t have before.”

This project highlights the importance of reassessing doctor-patient interactions, particularly in the context of palliative care. Another Keck medical student involved in the Immersive Memorials project, Jenny Ferrin, has shared how her participation in this initiative has influenced her medical education and her vision for the future of patient care.

“Being a medical student and just entering the hospital, I think a big thing that I’ve talked to some of my peers about is, even though we do everything ‘for the patient’, how often the patient’s humanity is forgotten,” Ferrin explained. “Obviously, in certain procedures, in certain situations, it’s more therapeutic to not grapple with someone’s humanity as you’re cutting them open for surgery or whatnot, but I have really found myself wondering this often.”

Ferrin also addressed how involvement in healthcare can lead to detachment from patients, raising concerns about the impact on both parties’ humanity.

“When you see so much in healthcare, you have to grapple with so much, or you have to do so many things to like other humans, like cutting them open for their benefit, it’s very easy to become detached, and I do wonder what impact that has on another person’s humanity,” Ferrin affirmed.

Gotsis also made a statement about the needs of healthcare professionals.

“The health professionals who take care of people in their last few months and weeks and days have a deep wish to know and remember something of people beyond their diagnosis and their struggle to cope with the losses that accumulate over time in practice,” Gotsis said.

Conclusion

The future of Immersive Memorials is promising, offering numerous opportunities for patients to manage their palliative care options and preserve their legacies. The aim is to transform these concepts into reality and create immersive experiences that honor and memorialize patients for eternity.

“Not everyone in the world has someone who can plan a legacy experience for another person, especially while they are still alive,” Gotsis pointed out. “Those who have state-sponsored people assigned to preserve legacies or loved ones who have some experience and capacity get this opportunity.”

USC Arts in Action is supporting the project for a second year, during which the team has switched to a bedside model of “media arts on behalf.” Additionally, the team has curated a pop-up installation at the clinic that will be installed on November 21st, is producing a toolkit for others who want to implement something similar, and plans to build more partnerships for sustainability.

The USC Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center (CM&BHC) is an organized research unit between the School of Cinematic Arts and the Keck School of Medicine.